Learning Objectives

By the end of this chapter, you should be able to:

- Explain the flow of API requests.

- Configure authorization rules.

- Examine authentication policies.

- Restrict network traffic with network policies.

SECURITY

Overview

Security is a big and complex topic, especially in a distributed system like Kubernetes. Thus, we are just going to cover some of the concepts that deal with security in the context of Kubernetes.

Then, we are going to focus on the authentication aspect of the API server and we will dive into authorization, looking at things like ABAC and RBAC, which is now the default configuration when you bootstrap a Kubernetes cluster with kubeadm.

We are going to look at the admission control system, which lets you look at and possibly modify the requests that are coming in, and do a final deny or accept on those requests.

Following that, we’re going to look at a few other concepts, including how you can secure your Pods more tightly using security contexts and pod security policies, which are full-fledged API objects in Kubernetes.

Finally, we will look at network policies. By default, we tend not to turn on network policies, which let any traffic flow through all of our pods, in all the different namespaces. Using network policies, we can actually define Ingress rules so that we can restrict the Ingress traffic between the different namespaces. The network tool in use, such as Flannel or Calico will determine if a network policy can be implemented. As Kubernetes becomes more mature, this will become a strongly suggested configuration.

Accessing the API

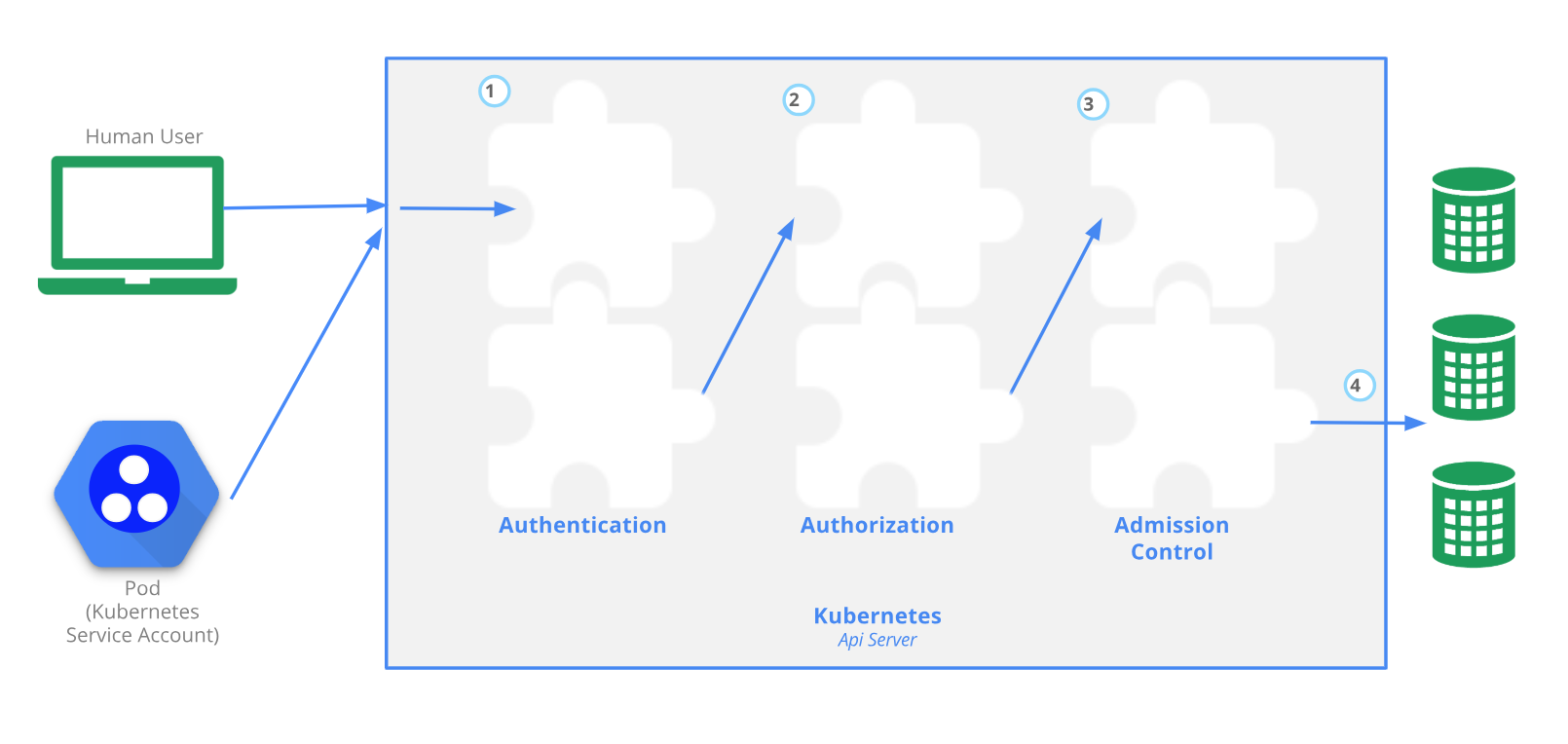

To perform any action in a Kubernetes cluster, you need to access the API and go through three main steps:

- Authentication:

- Authorization (ABAC or RBAC):

- Admission Control.

These steps are described in more detail in the official documentation about controlling access to the Kubernetes API and illustrated by the diagram below.

Accessing the API Retrieved from the Kubernetes website

Once a request reaches the API server securely, it will first go through any authentication module that has been configured. The request can be rejected if authentication fails or it gets authenticated and passed to the authorization step.

At the authorization step, the request will be checked against existing policies. It will be authorized if the user has the permissions to perform the requested actions. Then, the requests will go through the last step of admission. In general, admission controllers will check the actual content of the objects being created and validate them before admitting the request.

In addition to these steps, the requests reaching the API server over the network are encrypted using TLS. This needs to be properly configured using SSL certificates. If you use kubeadm, this configuration is done for you; otherwise, follow Kubernetes the Hard Way by Kelsey Hightower, or review the API server configuration options.

Authentication

There are three main points to remember with authentication in Kubernetes:

- In its straightforward form, authentication is done with certificates, tokens or basic authentication (i.e. username and password).

- Users are not created by the API, but should be managed by an external system.

- System accounts are used by processes to access the API (to learn more read Configure Service Accounts for Pods).

If you want to learn more on how system accounts are used by processes to access the API:

There are two more advanced authentication mechanisms. Webhooks can be used to verify bearer tokens, and connection with an external OpenID provider.

The type of authentication used is defined in the kube-apiserver startup options. Below are four examples of a subset of configuration options that would need to be set depending on what choice of authentication mechanism you choose:

–basic-auth-file

–oidc-issuer-url

–token-auth-file

–authorization-webhook-config-file

One or more Authenticator Modules are used:

- x509 Client Certs;

- static token, bearer or bootstrap token;

- static password file;

- service account;

- OpenID connect tokens.

Each is tried until successful, and the order is not guaranteed. Anonymous access can also be enabled, otherwise you will get a 401 response. Users are not created by the API, and should be managed by an external system.

To learn more about authentication, see the official Kubernetes Documentation.

Authorization

Once a request is authenticated, it needs to be authorized to be able to proceed through the Kubernetes system and perform its intended action.

There are three main authorization modes and two global Deny/Allow settings. The three main modes are:

- ABAC

- RBAC

- Webhook.

They can be configured as kube-apiserver startup options:

–authorization-mode=ABAC

–authorization-mode=RBAC

–authorization-mode=Webhook

–authorization-mode=AlwaysDeny

–authorization-mode=AlwaysAllow

The authorization modes implement policies to allow requests. Attributes of the requests are checked against the policies (e.g. user, group, namespace, verb).

ABAC, RBAC and Webhook Modes

-

ABAC

ABAC stands for Attribute Based Access Control. It was the first authorization model in Kubernetes that allowed administrators to implement the right policies. Today, RBAC is becoming the default authorization mode.

Policies are defined in a JSON file and referenced to by a kube-apiserver startup option:

–authorization-policy-file=my_policy.json

For example, the policy file shown below authorizes user Bob to read pods in the namespace foobar:

{ "apiVersion": "abac.authorization.kubernetes.io/v1beta1", "kind": "Policy", "spec": { "user": "bob", "namespace": "foobar", "resource": "pods", "readonly": true } }You can check other policy examples in the Kubernetes Documentation.

-

RBAC

RBAC stands for Role Based Access Control.

All resources are modeled API objects in Kubernetes, from Pods to Namespaces. They also belong to API Groups, such as core and apps.These resources allow operations such as Create, Read, Update, and Delete (CRUD), which we have been working with so far. Operations are called verbs inside YAML files. Adding to these basic components, we will add more elements of the API, which can then be managed via RBAC.

Rules are operations which can act upon an API group. Roles are a group of rules which affect, or scope, a single namespace, whereas ClusterRoles have a scope of the entire cluster.

Each operation can act upon one of three subjects, which are User Accounts which don’t exist as API objects, Service Accounts, and Groups which are known as clusterrolebinding when using kubectl.

RBAC is then writing rules to allow or deny operations by users, roles or groups upon resources.

While RBAC can be complex, the basic flow is to create a certificate for a user. As a user is not an API object of Kubernetes, we are requiring outside authentication, such as OpenSSL certificates. After generating the certificate against the cluster certificate authority, we can set that credential for the user using a context.

Roles can then be used to configure an association of apiGroups, resources, and the verbs allowed to them. The user can then be bound to a role limiting what and where they can work in the cluster.

Here is a summary of the RBAC process:

- Determine or create namespace

- Create certificate credentials for user

- Set the credentials for the user to the namespace using a context

- Create a role for the expected task set

- Bind the user to the role

- Verify the user has limited access.

-

Webhook

A Webhook is an HTTP callback, an HTTP POST that occurs when something happens; a simple event-notification via HTTP POST. A web application implementing Webhooks will POST a message to a URL when certain things happen.

To learn more about using the Webhook mode, see the Webhook Mode section of the Kubernetes Documentation.

Admission Controller

The last step in letting an API request into Kubernetes is admission control.

Admission controllers are pieces of software that can access the content of the objects being created by the requests. They can modify the content or validate it, and potentially deny the request.

Admission controllers are needed for certain features to work properly. Controllers have been added as Kubernetes matured. Starting with the 1.13.1 release of the kube-apiserver, the admission controllers are now compiled into the binary, instead of a list passed during execution. To enable or disable, you can pass the following options, changing out the plugins you want to enable or disable:

–enable-admission-plugins=Initializers,NamespaceLifecycle,LimitRanger –disable-admission-plugins=PodNodeSelector

The first controller is Initializers which will allow the dynamic modification of the API request, providing great flexibility. Each admission controller functionality is explained in the documentation. For example, the ResourceQuota controller will ensure that the object created does not violate any of the existing quotas.

Security Contexts

Pods and containers within pods can be given specific security constraints to limit what processes running in containers can do. For example, the UID of the process, the Linux capabilities, and the filesystem group can be limited.

This security limitation is called a security context. It can be defined for the entire pod or per container, and is represented as additional sections in the resources manifests. The notable difference is that Linux capabilities are set at the container level.

For example, if you want to enforce a policy that containers cannot run their process as the root user, you can add a pod security context like the one below:

apiVersion: v1

kind: Pod

metadata:

name: nginx

spec:

securityContext:

runAsNonRoot: true

containers:

- image: nginx

Then, when you create this Pod, you will see a warning that the container is trying to run as root and that it is not allowed. Hence, the Pod will never run:

$ kubectl get pods

NAME READY STATUS RESTARTS AGE

nginx 0/1 container has runAsNonRoot and image will run as root 0 10s

To learn more, read the Configure a Security Context for a Pod or Container section in the Kubernetes Documentation.

Pod Security Policies

To automate the enforcement of security contexts, you can define PodSecurityPolicies (PSP). A PSP is defined via a standard Kubernetes manifest following the PSP API schema. An example is presented below.

These policies are cluster-level rules that govern what a pod can do, what they can access, what user they run as, etc.

For instance, if you do not want any of the containers in your cluster to run as the root user, you can define a PSP to that effect. You can also prevent containers from being privileged or use the host network namespace, or the host PID namespace.

You can see an example of a PSP below:

apiVersion: policy/v1beta1

kind: PodSecurityPolicy

metadata:

name: restricted

spec:

seLinux:

rule: RunAsAny

supplementalGroups:

rule: RunAsAny

runAsUser:

rule: MustRunAsNonRoot

fsGroup:

rule: RunAsAny

For Pod Security Policies to be enabled, you need to configure the admission controller of the controller-manager to contain PodSecurityPolicy. These policies make even more sense when coupled with the RBAC configuration in your cluster. This will allow you to finely tune what your users are allowed to run and what capabilities and low level privileges their containers will have.

See the PSP RBAC example on GitHub for more details.

Network Security Policies

By default, all pods can reach each other; all ingress and egress traffic is allowed. This has been a high-level networking requirement in Kubernetes. However, network isolation can be configured and traffic to pods can be blocked. In newer versions of Kubernetes, egress traffic can also be blocked. This is done by configuring a NetworkPolicy. As all traffic is allowed, you may want to implement a policy that drops all traffic, then, other policies which allow desired ingress and egress traffic.

The spec of the policy can narrow down the effect to a particular namespace, which can be handy. Further settings include a podSelector, or label, to narrow down which Pods are affected. Further ingress and egress settings declare traffic to and from IP addresses and ports.

Not all network providers support the NetworkPolicies kind. A non-exhaustive list of providers with support includes Calico, Romana, Cilium, Kube-router, and WeaveNet.

In previous versions of Kubernetes, there was a requirement to annotate a namespace as part of network isolation, specifically the net.beta.kubernetes.io/network-policy= value. Some network plugins may still require this setting.

On the next page, you can find an example of a NetworkPolicy recipe. More network policy recipes can be found on GitHub.

Network Security Policy Example

The use of policies has become stable, noted with the v1 apiVersion. The example below narrows down the policy to affect the default namespace.

Only Pods with the label of role: db will be affected by this policy, and the policy has both Ingress and Egress settings.

The ingress setting includes a 172.17 network, with a smaller range of 172.17.1.0 IPs being excluded from this traffic.

apiVersion: networking.k8s.io/v1

kind: NetworkPolicy

metadata:

name: ingress-egress-policy

namespace: default

spec:

podSelector:

matchLabels:

role: db

policyTypes:

- Ingress

- Egress

ingress:

- from:

- ipBlock:

cidr: 172.17.0.0/16

except:

- 172.17.1.0/24

- namespaceSelector:

matchLabels:

project: myproject

- podSelector:

matchLabels:

role: frontend

ports:

- protocol: TCP

port: 6379

egress:

- to:

- ipBlock:

cidr: 10.0.0.0/24

ports:

- protocol: TCP

port: 5978

These rules change the namespace for the following settings to be labeled project: myproject. The affected Pods also would need to match the label role: frontend. Finally, TCP traffic on port 6379 would be allowed from these Pods.

The egress rules have the to settings, in this case the 10.0.0.0/24 range TCP traffic to port 5978.

The use of empty ingress or egress rules denies all type of traffic for the included Pods, though this is not suggested. Use another dedicated NetworkPolicy instead.

Default Policy Example

The empty braces will match all Pods not selected by other NetworkPolicy and will not allow ingress traffic. Egress traffic would be unaffected by this policy.

apiVersion: networking.k8s.io/v1

kind: NetworkPolicy

metadata:

name: default-deny

spec:

podSelector: {}

policyTypes:

- Ingress

With the potential for complex ingress and egress rules, it may be helpful to create multiple objects which include simple isolation rules and use easy to understand names and labels.

Some network plugins, such as WeaveNet, may require annotation of the Namespace. The following shows the setting of a DefaultDeny for the myns namespace:

kind: Namespace

apiVersion: v1

metadata:

name: myns

annotations:

net.beta.kubernetes.io/network-policy: |

{

"ingress": {

"isolation": "DefaultDeny"

}

}